|

The Voice behind KISS Grammar:

An Autobiographical Note |

|

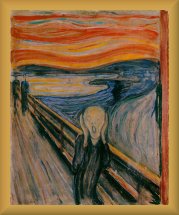

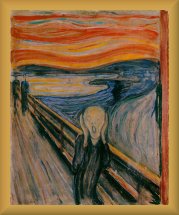

Edvard

Munch's

The Scream

1893,

National Gallery,

Oslo |

I don't really like writing about myself, but

you will find a voice in KISS Grammar, a voice that is usually absent in

most grammar books. In many of the analysis keys, for example, you will

find things such as "I would accept this explanation." Or "I expect students

to make a mistake here." The question, of course, is "Who is this 'I'"?

You will not find such statements in most grammar books. Most such books

are written as if grammar is a totally objective subject -- the book is

giving you the "facts."

If, however, you look at several different

books, you will probably become confused -- the "facts" change from book

to book. This happens because there is no "authoritative grammar" of English.

A grammar is simply a description of a language, and different grammarians

describe English in different ways, often using different terms. These

differences have caused tremendous problems in the teaching of grammar

in our schools, but that is discussed elsewhere on the KISS web site. The

questions to be addressed here are "Who is Ed Vavra?" "And why should anyone

pay attention to what he says?"

I teach five sections of Freshman English

every semester at Pennsylvania College of Technology. That is what I get

paid for, and that is where most of my time and effort is spent. My job

and my education are probably responsible, in large part, for my unique

perspective on the teaching of grammar. Every semester I work with students

who have major problems writing essays because they have major problems

with grammar, especially sentence structure. My education gave me a unique

perspective on the problem. In high school, and for a year in college,

I studied Latin, but my B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. are all in Russian Language

and Literature, with minors officially in Italian and French. I also had

to learn enough German to pass a reading test. Put differently, for me,

the

study of grammar is the study of a tool to be used for a purpose.

When, twenty or so years ago, I was asked

to teach a grammar course for future teachers, I looked at the English

grammar textbooks and soon realized that none of these books has a purpose.

They taught, and still teach, isolated concepts, terms, and countless exceptions

to the rules. Although some of these books (and their writers) claim that

their purpose is to improve students' writing, the claims are vague, and

I have yet to see any book that even claims to try to enable students to

analyze and discuss the structure of their own sentences. Indeed I have

yet to see any book that even claims to try to teach students how to identify

the subjects and verbs in their own writing. To me, this does not make

any sense at all. Thus, the KISS Approach was born.

To test my ideas, and to share

ideas with others, I founded, and for fifteen years served as editor

of, Syntax in the Schools, the only national publication

dedicated to the teaching of grammar. Syntax is now the official

publication of the Assembly for the Teaching of English Grammar, an assembly

of the National Council of Teachers of English. In other words, I have

been heavily involved in "The Great Grammar Debate" for over twenty years.

During these years, I published several short articles in English Journal.

but I have become convinced that the teachers (professors) of future teachers

and the major educational organizations such as NCTE are not really interested

in helping students.

The preceding summary should suggest that

I have some idea of what I write about. In composition courses such as

the one I teach, my credentials are called an appeal to authority.

Does the writer (or speaker) have a demonstrated expertise in the topic?

But, if you care about my credentials at all, I ask that you use them only

as a reason to begin to examine KISS Grammar. The primary appeal

of KISS Grammar is to what, in composition classes, we call logic. More

simply, it is an appeal to common sense.

Even if you are familiar with grammatical

terms, you will probably be initially confused by KISS Grammar because

KISS is an entirely different way of looking at the teaching of grammar.

All you need to do to see this difference is to compare the other textbooks

with KISS instructional materials and exercises. Not only do most grammar

textbooks not teach grammar effectively -- they kill it, slice it, and

dice it. (Is it any wonder that students -- and most teachers -- hate it?

Dead stuff stinks.)

Look at the "Tables of Contents" in almost

any grammar book. You will probably find a chapter on "Parts of Speech,"

a chapter on "Basic Sentence Structure," chapters on verbs and verb forms,

chapters on clauses, etc. Prepositional phrases, one of the most important

constructions for students to understand if they are to see how a living

language works, are usually relegated to a chapter near the end of the

book. And the chapters are all separated and illustrated with very simplistic

examples. There is no discussion of how all these parts fit together. Each

chapter is a diced and sliced section (of a living language) as if it were

dead and on a dissecting table.. Ouch! Rarely, if ever, will you find a

single, relatively complicated sentence analyzed in full.

KISS exercises, on the other hand, are often

either complete works (or verbatim, consecutive passages from longer works).

Instruction proceeds through several levels, and by the last level, the

grammatical function of every word in every sentence in every passage has

been explained. As they learn how to do this analysis, students begin to

understand not only why many errors are, in fact, errors, but also how

sentence structure affects writing style and logic. Having mentioned errors,

style, and logic, I would like to address a question that I am frequently

asked by teachers and parents who are considering the KISS Approach --

When does KISS address punctuation and other errors?

The only way to effectively address these

errors is to understand what punctuation does -- how does it "work" in

sentences? And the only way to understand that is to understand how sentences

work. And the only way to do that is to spend some time learning to recognize

adjectives, adverbs, prepositional phrases, and subjects, verbs, and complements

-- not just in the simplistic sentences found in most grammar books, but

in real texts such as those in the KISS exercises. In The Karate Kid,

Daniel objects to waxing the car and painting the fence -- "Wax on. Wax

off. Wax on. Wax off." It's boring, and Daniel wants to quit. But after

he has done it, Mr. Miyagi easily shows him how important those tasks were.

The initial levels of KISS Grammar can be made much less boring than waxing

a car and painting a fence, and they are crucial.

Thus far I have asked you to pay brief attention

to my credentials and then to judge the KISS Approach in terms of whether

or not it makes sense to you. The latter also applies to the terminology

used in KISS Grammar. Confusion about terminology is a major problem in

the teaching of grammar. KISS Grammar has a name because the name designates

a systematic, limited set of grammatical terms and concepts that enable

students to discuss the function of any word in any sentence. Most of the

terms used in KISS are traditional, but some, for reasons that are explained

both in the instructional materials and in the notes, are distinctly KISS

concepts. Are these KISS concepts "correct"? You can, of course, compare

them with what you can find in other grammar books, but I would suggest

that the more important question is "Do they make sense to you?" Do you

want a name for a concept? Or do you want to understand how words work

together to make meaning in sentences?

KISS owes a great deal to the research and

theories of Kellogg Hunt, Roy

O'Donnell, and Walter Loban,

to the developmental theories of

Lev

Vygotsky, Jean Piaget, and Jerome

Bruner, and to a psycholinguistic

model of how the brain processes language, a model that is based on

George

Miller's fundamental work on short-term memory. I also want to thank

the many students who helped develop KISS Grammar, and members of the KISS

List, whose questions have helped me not only improve many of the instructional

materials but also restructure their presentation. All these instructional

materials are free. I don't want more money (although my family could probably

use it). And I don't want fame. I want to change the way grammar is taught

-- across this country, and around the world. I'm passionate about that.

(Note the illustration on this page.) Our students (and their teachers)

deserve better than what we have been giving them.

|